I was a scientist from a very early age. And a culinary adventurer as well. I grew up on the shores of Lake Mendota, a lovely lake surrounded by the city of Madison, crystal clear in the fall and spring, and thickening to a rich organic green by summer. As a child, in the summer, when I wasn't Ariel, draped across the big rock near the

shore, singing my head off, I was scheming about feasting on my undersea

garden.

This plan came to fruition, conveniently, while my entire extended family was in Madison for a reunion (a plan which none of them seem to have forgotten). I'd heard of seaweed being served in Japanese cuisine, and felt that there was no reason why we shouldn't be able to make due with what we had- the bounty of Lake Mendota.

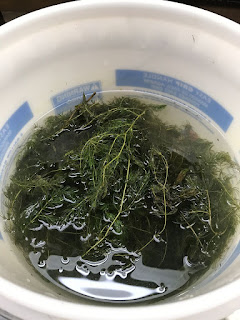

From the green tinted waters of this pristine lake, I collected a heaping pile of seaweed. And everyone knows that random aquatic weeds hauled from a lake nurtured by agricultural runoff are better off cooked, so into the spaghetti pot it went. It looked, I recall, a bit like this:

The first thing that came to my attention, and that of the gathered crowd of curious aunts and uncles, was the hordes of small squirming things floating to the top of the water. The whole mass was covered with tiny wriggling dots of unknown taxonomy. Suddenly, my verdant spaghetti had lost its appeal.

Actually, the above picture was taken this summer, when I learned what those creatures were...and then counted them. I had finally escaped the magnetic pull of Madison, and landed a job at a world-class museum in the big city. Which sent me...back to Madison to do research and collaborate with the UW Entomology Department. And soon enough, I was back in the lake, looking for all of the squirmy critters I could find.

What is an entomologist doing swimming around in a lake, you might ask, working out of a Limnology boat and collecting, well, seaweed? It turns out that many insects spend a majority of their lives in an immature "nymph" (more specifically "naiad") stage underwater. Some dragonfly nymphs spend up to four years living beneath the waves in this form, and only live for a few months as the more recognizable flying adults. Dragonflies, caddisflies, stoneflies, mayflies, midges, mosquitos, and some moths (yep, moths) to name a few, live a good chunk of their lives in bizarre, unrecognizable forms, complete with gills, beneath the surface.

Here's a brief gallery (not my photos) of some of these strange and alien critters, from the armored stonefly to the roaming peddler of the caddisfly with its insatiable need to collect all the things and stick them to itself. I'll introduce a few of my favorites in more detail in a later post.

And these insects prefer particular types of plants, as monarchs do milkweed, or ants do acacia trees. They use them for food, for shelter, for building material, and as something to hang on to when the current gets fast or the waves get big. Therefore, to collect these insects we collected seaweed, and tried to determine which insects clung to which plants (macrophytes), and which drifted in the space-like void of the open water. A survey of our haul brought back echos of my childhood gastronomic escapades.

After we gathered the vegetation, all of those tiny squirming things that had once tried to escape that spaghetti pot were separated and counted and catalogued and databased and put into glass vials with teeny tiny labels to be kept in the museum for posterity. I know too well now what the contents of that pea green Lake Mendota summer bisque are. Tiny shrimp-like amphipods, multicolored globular water mites, odd round daphnia, and an occasional graceful damselfly naiad were among the things that zoomed and swirled and wriggled to the surface.

In 1938, a PhD student did a very thorough study on these aquatic macroinvertebrates (spineless critters that one can see without a microscope) in Lake Mendota and the plants that they were associated with. 80 years later, we asked "what has changed?" We followed that student's original methods closely (except for a few updates like high-powered outboard motors and Google Docs) and are comparing our data with his. Keep in mind that Eurasian Water Milfoil, that habitat-distrupting, propeller-clogging scourge of a plant did not arrive in Wisconsin until the 1960's.What did that do to the insect diversity? The data is being analyzed now, and hopefully the mystery will be uncovered- or dozens of new unanswered questions will be sparked (hooray for science!)

But summers pass and so does grant funding, and I have hung up my wetsuit and now turned in my badge at the Field Museum, sadly. I hope to be back someday if the opportunity presents itself. But I have left my mark on the place (literally, with my name typed dozens of times in 2-point font and submerged in alcohol in tiny vials somewhere). I have come away with a much greater knowledge and appreciation of the critters of Lake Mendota, museum curation skills, some tech know-how, contacts with a host of interesting entomologists, and a desire to never ever count another damned amphipod again.

And, for the record, I thoroughly enjoy the actual ocean seaweed that I get in Japanese restaurants.

This plan came to fruition, conveniently, while my entire extended family was in Madison for a reunion (a plan which none of them seem to have forgotten). I'd heard of seaweed being served in Japanese cuisine, and felt that there was no reason why we shouldn't be able to make due with what we had- the bounty of Lake Mendota.

From the green tinted waters of this pristine lake, I collected a heaping pile of seaweed. And everyone knows that random aquatic weeds hauled from a lake nurtured by agricultural runoff are better off cooked, so into the spaghetti pot it went. It looked, I recall, a bit like this:

The first thing that came to my attention, and that of the gathered crowd of curious aunts and uncles, was the hordes of small squirming things floating to the top of the water. The whole mass was covered with tiny wriggling dots of unknown taxonomy. Suddenly, my verdant spaghetti had lost its appeal.

Actually, the above picture was taken this summer, when I learned what those creatures were...and then counted them. I had finally escaped the magnetic pull of Madison, and landed a job at a world-class museum in the big city. Which sent me...back to Madison to do research and collaborate with the UW Entomology Department. And soon enough, I was back in the lake, looking for all of the squirmy critters I could find.

Here's a brief gallery (not my photos) of some of these strange and alien critters, from the armored stonefly to the roaming peddler of the caddisfly with its insatiable need to collect all the things and stick them to itself. I'll introduce a few of my favorites in more detail in a later post.

And these insects prefer particular types of plants, as monarchs do milkweed, or ants do acacia trees. They use them for food, for shelter, for building material, and as something to hang on to when the current gets fast or the waves get big. Therefore, to collect these insects we collected seaweed, and tried to determine which insects clung to which plants (macrophytes), and which drifted in the space-like void of the open water. A survey of our haul brought back echos of my childhood gastronomic escapades.

|

| Glamorous field work in the sparkling pristine waters of Lake Mendota |

In 1938, a PhD student did a very thorough study on these aquatic macroinvertebrates (spineless critters that one can see without a microscope) in Lake Mendota and the plants that they were associated with. 80 years later, we asked "what has changed?" We followed that student's original methods closely (except for a few updates like high-powered outboard motors and Google Docs) and are comparing our data with his. Keep in mind that Eurasian Water Milfoil, that habitat-distrupting, propeller-clogging scourge of a plant did not arrive in Wisconsin until the 1960's.What did that do to the insect diversity? The data is being analyzed now, and hopefully the mystery will be uncovered- or dozens of new unanswered questions will be sparked (hooray for science!)

But summers pass and so does grant funding, and I have hung up my wetsuit and now turned in my badge at the Field Museum, sadly. I hope to be back someday if the opportunity presents itself. But I have left my mark on the place (literally, with my name typed dozens of times in 2-point font and submerged in alcohol in tiny vials somewhere). I have come away with a much greater knowledge and appreciation of the critters of Lake Mendota, museum curation skills, some tech know-how, contacts with a host of interesting entomologists, and a desire to never ever count another damned amphipod again.

And, for the record, I thoroughly enjoy the actual ocean seaweed that I get in Japanese restaurants.

Comments

Post a Comment